Now housed in the Prince’s Palace in Copenhagen, the National Museum of Denmark has one of the oldest established collections of prehistoric artefacts in the world. It dates back to King Frederik VI, who set up Den Kongelige Commission til Oldsagers Opbevaring (The Royal Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities) in 1807. One early secretary of the Royal Commission, Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (he held the position from 1816) used its rich holdings of Danish antiquities to develop his ‘Three Age’ system for prehistory, dividing it up into the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. More than 200 years after the Commission’s founding, the ground floor of the Prince’s Palace (where the collection moved in 1855) beautifully presents artefacts from across Denmark, which offer a detailed look at the people who lived there, as well as further objects from the land that once connected Denmark to Britain (now submerged by the North Sea). Covering thousands of years of occupation, the holdings provide some interesting insights into different beliefs over time. Perhaps the most famous of the museum’s exhibits relating to beliefs in prehistory is the stunning Bronze Age sun chariot, discovered in fragments during the ploughing of a field in Trundholm Bog in 1902. Dating to c.1350 BC, this 60cm-long statue consists of a horse pulling a circular disc (with one side covered in gold foil) that represents the sun. Both the horse and the sun are mounted on wheels, and so could have been moved during a ceremony. The motif of the Sun Horse is one seen elsewhere in Bronze Age Scandinavia, such as on bronze razors (all images of men from Bronze Age Denmark show them clean-shaven) and in rock carvings from Sweden and Norway.

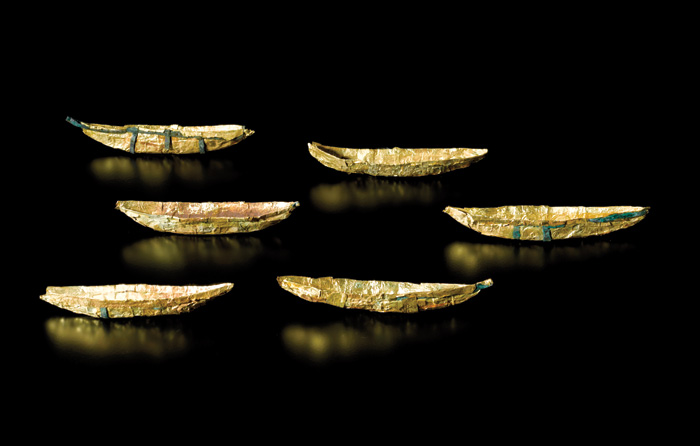

The divine horse was not the only thing that helped the sun on its passage. In Denmark, the sun appears to rise from and set into the sea, so one belief was that during the night a ship carried it through the darkness of the underworld. In the morning, the fish and the bird would release it from the ship; during the day, the horse would pull it through the sky; and in the evening the snake would guide it back onto the ship again. The Sun Ship is another image seen on razors, but it is recreated in gold in the form of miniature model boats too. Dozens of these small, shimmering ships, from Nors and probably dating from 1500-1100 BC, are on display. Some are even decorated with concentric circles, probably representing the sun. Not all prehistoric ships are associated with the sun. The ship became the most common motif in Bronze Age imagery from around 1700 BC. It is seen carved in rocks from Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. The oldest ship image from Denmark, though – shown with a set of lines making up its crew – appears on a curved sword from Rørby dating from c.1600 BC. Bogs, burials, and beliefs

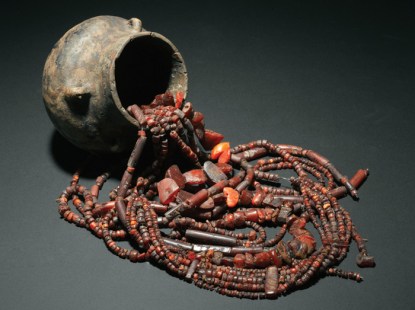

Long before these images, pieces of amber collected on the coasts of Jutland were worked into jewellery, carved into animals, and engraved with lines. Pendants with signs of heavy wear, dating as far back as 8000-7000 BC, have been found washed up on the shores, while other amber artefacts, like beads, have been recovered en masse from a single deposition. In Sortekær Bog, one pottery vessel was found full of 1,720 amber beads (weighing in at 8.5kg), which appeared to have been deposited as an offering.

Later, in Iron Age Denmark, there are many signs of contact with the Roman Empire, including in the religious sphere. A richly furnished 4th-century AD burial of a woman was discovered in Årslev in 1820, containing, among fine jewellery, a Roman silver spoon and Roman tableware. The grave also contained a small, clear ball made of rock crystal, with an intriguing inscription in Greek: an abbreviation of the palindrome ‘ablanathanalba’. This inscription is seen on amulets and cameos associated with Gnosticism. The crystal ball carries the early Christian symbol of the anchor, too, which may hint that the woman was a Christian, and, if so, was one of the first believers in Denmark. Other Christian symbols became more prominent in the centuries to come, with crosses appearing even on axes in the Viking Age. By the 10th century AD, parts of the population had adopted Christianity, while others still worshipped the gods of the Norse pantheon. One object that neatly encapsulates this coexistence of multiple faiths is a mould used to make both Christian crosses and Thor’s Hammers, which become popular in the 10th century, perhaps in response to the spread of Christianity at the time.

The level of preservation of many of the displays is breathtaking. In some cases, woolen blankets, animal hides, and even clothing have survived for thousands of years, almost intact, within Bronze Age oak coffins. As well as what they may have believed, we can see clearly what people wore, and with new research providing details about individuals’ life stories, the museum brings us up close to Denmark’s ancient inhabitants.