Four hundred years ago, on 6 September 1620, the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth in the United Kingdom on a journey to the ‘New World’ that would become one of the most-famous stories in American history. To commemorate the 400th anniversary of the voyage, a new museum in Plymouth has launched a commemorative exhibition about the Mayflower, with more than 400 objects from across four nations and four centuries, setting out to tell the story of the ship and its passengers, and to dispel some of the myths and misconceptions that have surrounded it over time. The Box is a new museum, gallery, and archive in Plymouth, Devon, designed to celebrate the city’s heritage. The museum, which opened on 29 September 2020, pays homage to the maritime and international connections of ‘Britain’s Ocean City’, with nine permanent galleries encompassing natural history and art collections, extensive archives, and a wealth of artefacts celebrating the city’s long history as a port. The Mayflower 400 exhibition is a collaborative project, with artefacts on loan from locations across the UK, the US, and the Netherlands. According to the curator, Jo Loosemore, the goal was to create a display incorporating the wider context of the journey and correcting many of the inaccuracies that are present in the popular understanding of the Mayflower’s story today. Although the ship takes centre stage, with a large abstract structure representing the Mayflower that visitors can enter running down the middle of the exhibition space, it is surrounded on either side by exhibits highlighting the historical conditions that led to the journey taking place, and the events that unfolded after the ship’s arrival in America. On entering the gallery, visitors are reminded that, despite their prominence in the story of the early colonists, the passengers of the Mayflower were not the first Europeans to settle in the ‘New World’. Their journey was part of a long history of interaction between England and America – from the colony at Roanoke, established (and lost) under Elizabeth I, to the first enduring settlement at Jamestown and the forgotten colony of Popham. The exhibition also stresses that the arrival of English colonisers did not represent the beginning of ‘American history’, as the presence of Native Americans whose ancestors have lived there for more than 12,000 years emphasises. In the main exhibition space, a series of books and paintings illustrate the changing political and religious landscape in England at the start of the 17th century, which prompted the Separatists (a group of Puritans who rejected the Church of England) to escape to Leiden, before the conditions there prompted them to embark on the journey to America in 1620. The Separatists purchased a ship called the Speedwell and travelled to Southampton in Hampshire, where they were to meet the Mayflower, carrying other passengers from London, before making the journey across the Atlantic. However, the second leg of the voyage got off to a rough start, as leaks in the Speedwell forced both ships to turn back multiple times, and eventually led to the Speedwell being abandoned at Plymouth, with some of its passengers transferring to the Mayflower. Inopportune winds brought further delays, and the Mayflower finally set sail, alone, on 6 September, in gruelling autumn conditions. All aboard The ‘ghosts’ of the passengers of the Mayflower are a powerful presence in the exhibition space: a crowd of figures in silhouette, created through the ingenious use of layered fabric. Information about the individuals runs along the floor at their feet, from William Mullins, a shoemaker from Dorking who is believed to have travelled with 250 shoes, to Susanna White, one of three pregnant women on board, who gave birth to Peregrine (meaning ‘traveller’) off the coast of America.

Just like the passengers themselves, the next step for visitors to the exhibition is to enter the large ship structure to discover more about the construction, crew, and navigation of the Mayflower, with examples of astrolabes, backstaffs, maps, and globes of the type that may have been used to guide them to their destination. The structure offers a spatial simulation of the proportion of ship space each passenger might have had – which suggests the voyage would have been a fairly unpleasant experience if you were tall or claustrophobic – and some artefacts showing how they may have spent their 66 days at sea, including books, dice, and spinning tops. A board at the exit from the ship details its arrival, not at the intended destination on the Hudson River but at Provincetown, Massachusetts, and the signing of the Mayflower Compact, a set of rules for self-governance, by 41 of the male passengers before they went ashore. This committed them to ‘the good of the colony’, wherever they settled. As you leave the ship, you are immediately confronted by the harsh reality of conditions, including disease, malnutrition, and the brutal New England weather, that resulted in the deaths of over half of those who travelled on the Mayflower within the first year of their arrival.

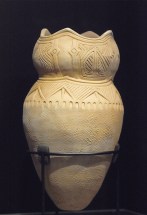

Also prominently displayed is a selection of artefacts highlighting the culture of the indigenous Wampanoag people who were living in the region when the Mayflower arrived, including a new piece of pottery commissioned for The Box. The museum’s partnership with the Wampanoag Advisory Committee to Plymouth 400 has allowed them to work together to ensure that the story of the Wampanoag Nation is told throughout the exhibition. The myth of the Mayflower Despite the difficult origins of the settlement at Plymouth, Massachusetts, it grew over time, with more settlers arriving there (and at other locations in New England) over the next century. Material evidence of their presence can be seen in a case containing pieces of West Country pottery found at a range of early colonial sites, as well as a North Devon ceramic tile bearing a Native American design, indicating more cooperation between the groups than is often described. The English settlers also recorded their experiences in books promoting the colonies, thus setting in motion the mythology that would grow to envelop the Mayflower.

This legacy is examined in the last room of the exhibition, demonstrating how the voyage has been seen through history, from Victorian paintings depicting the passengers as Romantic heroes to a 1967 magazine cover portraying the ‘Men of the Mayflower’ as daring adventurers. Many of the inaccuracies present in these popular renditions of the Mayflower’s story are apparent thanks to the earlier sections of the exhibition, which deliberately draws on contemporaneous sources alone. Although some aspects of the story have been embellished over time, the ongoing importance of the Mayflower is demonstrated by the final wall of the exhibition, which depicts the faces of 1,000 living Mayflower descendants, for whom a connection with the ship still holds great significance. Also acknowledged, however, is the lasting impact that the Mayflower’s arrival had on the Wampanoag people. Mayflower 400: Legend & Legacy presents this renowned voyage in a refreshing and engaging new light, demonstrating both the enduring power of historical stories and the necessity of re-examining them.