Three thousand years of daily life in Rome

Fresh traces of urban life spanning almost three millennia are coming to light in central Rome. New Danish-Italian excavations have uncovered far more than Caesar’s monumental forum project. Delving through archaeological layers, while traveling back in time from Mussolini’s 1930s constructions, Jan Kindberg Jacobsen, Eva Mortensen, Claudio Parisi Presicce, and Rubina Raja disentangle the complex urban stratigraphy of the Eternal City.

For some years, the buzzing sound of mechanical digging has been emanating from a green-screen enclosure standing beside Rome’s monumental avenue, the Via dei Fori Imperiali. This is because an excavation site lies entrenched between the broad avenue and the adjacent portion of Caesar’s Forum, which is open to the public as part of an archaeological park. There, in the southeastern section of the complex, heavy mechanical excavators and trucks operate alongside archaeologists, conservators, geologists, and radiocarbon specialists, who are committed to figuring out what was going on here in the past. Inside the enclosure, two trenches are cordoned off with plastic fences that proclaim there are ‘lavori in corso’: works in progress. Sure enough, our team has reached deep into the archaeological layers, revealing an incredible amount of new knowledge about the long history of Rome. This work is taking place in the heart of the city. The Roman Forum lies close at hand, while the remains of the imperial fora established by the emperors Augustus (reigned 27 BC to AD 14), Nerva (reigned 96-98), and Trajan (reigned 98-117) are visible on the far side of the Via dei Fori Imperiali. Over the recent winter months, trowels and buckets were stowed away, and the Bobcat excavator rested, surrendering the site to restoration specialists and architects. Meanwhile, the archaeologists find specialists, and soil scientists headed indoors to study the excavated material and process a wealth of samples. Together, their findings can lead us from the 20th century AD back to the 6th century BC.

Clean up first, then demolish

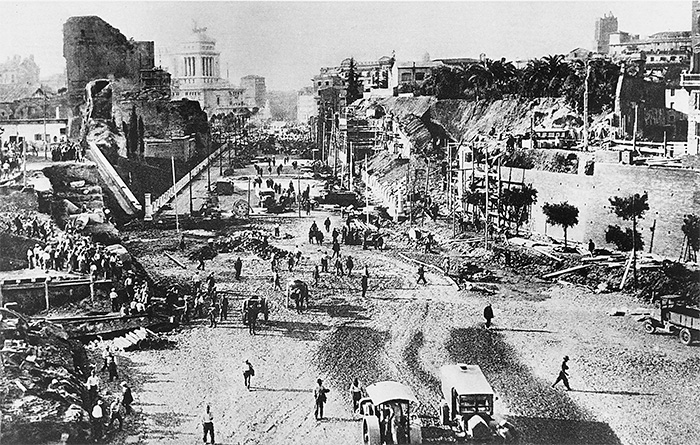

Our journey starts on 28 October 1932, when the Via dei Fori Imperiali, which today leads people from Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum, was inaugurated by Benito Mussolini. Back then it was called the Via dell’Impero, a parade street that simultaneously celebrated the ideology of the fascist regime and physically connected it to Rome’s ancient and glorious past. The street cut through the late Republican Forum of Caesar and all of the imperial fora. When this new thoroughfare was first planned, though, most of the Roman-era remains were obscured beneath a densely inhabited residential area known as the Alessandrino Quarter. Its housing blocks were razed together with five churches, causing about a thousand families to be evicted and rehomed in newly built neighborhoods on the outskirts of Rome. Once exposed, most of Caesar’s Forum was excavated, alongside portions of the other fora. Speed was the defining quality of this work, though. After just a year and a half of demolition and excavation, the center of Rome lay transformed. Afterward, its appearance before this intervention by the fascist regime was soon largely forgotten, with most modern visitors never realizing that the ruins looked radically different less than a century ago. Fortunately for us, the area currently being excavated in Caesar’s Forum was not dug out at that time. Neither was it overbuilt by the parade street because Mussolini needed a turning space for his grandiloquent parades.

The Alessandrino Quarter had a long pedigree. It was first established in the second half of the 16th century, meaning that it’s three- to four-story high housing blocks had accommodated part of Rome’s fast-growing population for over three centuries. While it has always been possible to get a sense of the Alessandrino Quarter from photographs, historic maps, and written sources, prior to our excavations very little was known about the material culture of daily life. Indeed, even then it has not always been easy to bring its former inhabitants into sharp focus. Not only did they take their possessions with them when they vacated their homes, but they also scrupulously swept the floors – even though the buildings were about to be torn down. This compulsion for cleanliness was not just a matter of pride. Instead, it can be explained by a pending inspection from the state architects, who were brought in to make precise measurements of the apartments. This was important for the families, in order for them to receive the correct compensation from the state, after being forced to leave their homes.

Naturally, such sprucing up did not extend to hidden spaces like underground sewers and channels, allowing traces of the last inhabitants to survive there. Systematic excavation and recording of these spaces is granting insight into the residents’ domestic activities, social standing, and even their diet. Pieces of jewelry and shirt buttons made of bone probably entered the sewers accidentally when washing clothes, whereas plates, forks, and glasses must have come from one or more kitchens above. Animal bones, mostly from pigs, alongside the many mussel shells and chicken eggs found, tell us about the dietary habits of the inhabitants. In addition, the excavations allow us to understand the practical manner in which the buildings were demolished and the rubble discarded – often packed into sewers or used to level off cellars. We even found the tools and personal belongings of the workmen who carried out the demolition.

The remains of some rooms in the housing blocks were also preserved. Here, the floors are of interest, as, far from being uniform, different materials were employed and different patterns were created. These allow us to chart shifts in architectural fashions and the impact of modernization over the course of three centuries. From these floors emerges a narrative whereby Renaissance houses were rebuilt during the second half of the 19th century to install modern commodities, including electricity and flushable toilets. While we lack small finds from the rooms, the floors are still a great help when it comes to deducing what these spaces were used for. After all, the different demands of domestic living quarters, kitchens, and laundries often result in distinctive flooring.