Exploring life and death in a desert city

What can an extraordinary group of sculptures commemorating the dead reveal about ancient life in Palmyra? Thousands of ancient inhabitants’ portraits once graced lavish family tombs in cemeteries just beyond the desert city. Studying this artistry can reveal much about wealth, power, family, and even the balance between local tradition and outside influences in a major trading hub, as Eva Mortensen and Rubina Raja reveal.

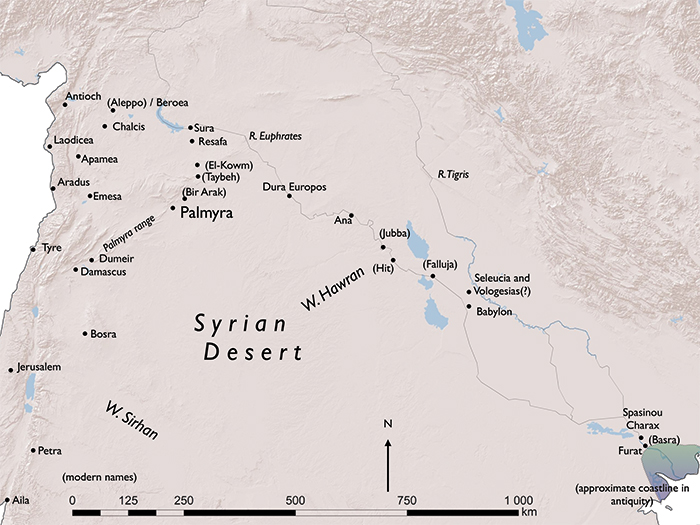

You will almost certainly have heard of Palmyra. This ancient oasis and caravan city lies in the middle of the Syrian Desert and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1980. Sadly, over the last decade most of the news from the site has concerned the heart-breaking loss, of both people and archaeology, during the devastating civil war in Syria. But even if you have never had a chance to visit Syria, you may well have become acquainted with one or more of the Palmyrenes of the past. This is because thousands of limestone portraits of Palmyra’s ancient inhabitants are scattered across museums and collections all over the world. Since 2012, a team of researchers based at Aarhus University, Denmark, has been studying these funerary portraits. Not only do they allow us to put a face to thousands of Palmyrenes, but they also reveal a great deal about their lives and culture, which were shaped by strong traditions and very particular local circumstances. The Palmyrenes lived in an oasis surrounded by many miles of steppe desert, with hours of arduous travel necessary to reach any other large – or even small – city, such as Damascus to the west and Dura-Europos to the east. An additional factor adding flavour to local life is that the Palmyrenes lived in what became a border region between the Roman and the Parthian empires: two major powers who often entered into direct competition with each other. Despite lying on the fringes of these empires – or perhaps precisely because of that – the Palmyrenes retained a distinctive identity during more than 300 years of Roman rule, while their city flourished as a trading hub between East and West. Unsurprisingly for an oasis city, Palmyra was a major player in the camel caravan trade, but it also had a hand in maritime exchange via the Euphrates, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean.

Inevitably, exposure to outside influences helped shape such a proud trading city, but the Palmyrenes also remained true to their own local customs and particular ways of life. Even so, focusing on the first three centuries AD reveals that the Palmyrene respect for tradition was balanced by a talent for agility. Long-term climate change, economic fluctuations, and new ruling empires, as well as unforeseen crises such as epidemics or political and military upheavals, required an ability to adapt in order to stay on top of business. At the same time, the city’s distance from other urban centres required a willingness to use and reuse certain resources in creative ways.

Urban Palmyra

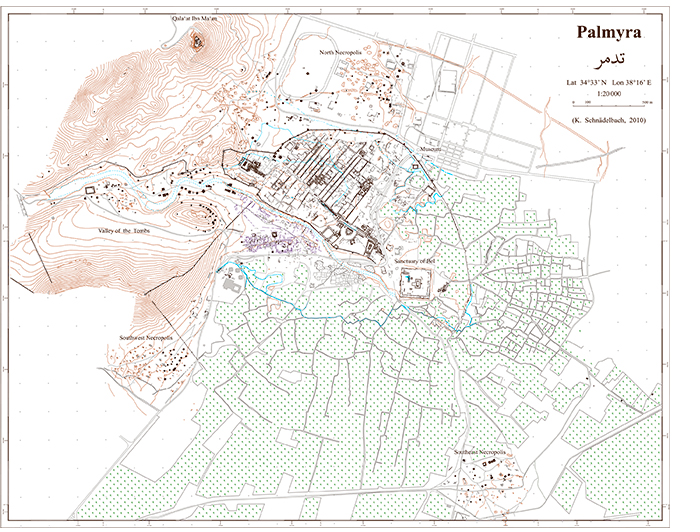

The people of Palmyra lived in a city that became embellished with splendid monuments, including magnificent temple complexes, broad colonnaded avenues, a large theatre, bath complexes, an agora, and a triumphal arch. Just beyond the urban area, large plots were set aside as burial places, with four extensive necropolises forming the final resting place for ancient Palmyrenes. As these cemeteries lay along the main access routes to the city, their tombs would be the first thing that locals and foreigners alike were confronted with when approaching the settlement.

During its heyday, caravans would have been a regular sight in Palmyra – or more likely just outside its urban area. There, we can imagine a miasma of perfume, spices, wine, and salted fish, mixed with the smell of damp camels and donkeys – along with their faeces – wafting over the caravan station. Donkeys and camels would have arrived and departed frequently, carrying slaves, prostitutes, wool, different types of dry goods such as nuts and dried fish, or alabaster jars and goat skins filled with perfumed oil and olive oil. The leading lights of this enterprising trade were the socialite Palmyrene male population, who were also exactly the kind of high-status individuals portrayed in the ancient funerary sculptures.

It was during the first three centuries AD that urban Palmyra took on its familiar form, as the prosperous settlement grew rapidly. The city had been annexed by the Roman Republic in the 60s BC, after Pompey the Great swept through the region with his army. Palmyra was destined to remain under Roman control for most of the next seven centuries, until the Arab invasion in AD 634 brought a new political regime. The long years of Roman rule did not pass unbroken, though, as Palmyra rebelled against its overlords in the late 3rd century and succeeded – for a short while – in casting them off. For a few years, the city ran its own affairs, but when the reckoning came it cost Palmyra everything.

Zenobia, a Palmyrene ruler, led the rebellion against Rome. The origins of this affair lie in the assassination of her husband, Odaenath, in AD 267 or 268, while he was campaigning against the Sassanians. Odaenath had been an important Roman ally and successful military leader, but when Zenobia took power to rule on behalf of their son, Vallabath, who had not yet come of age, she established an independent Palmyrene Empire. Under Zenobia, Palmyra’s territory expanded dramatically and ultimately included parts of Asia Minor and Egypt. This placed Palmyra in control of infrastructure that was key to Rome’s regional interests, setting the city on a collision course with its former rulers. In the end, Zenobia’s disruption of the geopolitical situation lasted for just a few years, with the Roman emperor Aurelian besieging Palmyra and capturing Zenobia in AD 272. The Palmyrenes attempted a second uprising in AD 273, but it was swiftly suppressed, and this time the city was sacked, and many members of its rebellious forces were executed. Although the city still existed in the aftermath, it lost both its political clout and influence over regional trade networks. The city retracted immensely, probably because its population dwindled after many erstwhile inhabitants turned to life in the rural hinterland of Palmyra. Although Palmyra ultimately became a much smaller settlement, it was never truly forgotten. Both ancient Palmyra and its limestone sculptural reliefs have received attention from archaeologists and art historians for over a century. But even before the first excavations commenced during the early 20th century, it was a well-known site. Written sources, mostly dating from late antiquity onwards, told the tale of this oasis city and its rebel queen, drawing in western travellers on 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century grand tours. In turn, the romantic ruins became a focal point for literature, music, and the painted arts. It was also in the late 19th century that Palmyrene relief sculptures began being shipped overseas, destined for museums and private collections. Among the former, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen and the Musée du Louvre in Paris were the first European museums to acquire large collections of Palmyrene funerary portrait sculptures.

A key moment for their study came in the 1920s and ’30s, when the Danish archaeologist Harald Ingholt investigated numerous tomb complexes outside Palmyra. He was working in collaboration with a French team, under a concession granted through the French Mandate in Syria, and was inspired to undertake the first comprehensive study of the iconography and chronology of the portrait reliefs. This was published in Danish as his higher doctoral dissertation in 1928. So it was that upper-class Palmyrenes came to play an important role again – this time in the study of Roman-period portraiture. Over the last decade, around 4,000 portraits of upper-class Palmyrenes have been extensively studied by the Palmyra Portrait Project, based at Aarhus University. It is absolutely exceptional to have such a large surviving corpus of sculptural material from a single location in the ancient world. These portraits were created over a period of around 300 years, and all of them were commissioned to commemorate the dead. A database with photographs and descriptions of every single portrait has been compiled and will soon be published. This corpus brings us face to face with thousands of wealthy Palmyrenes, while the research it generated has also provided fresh insights into economic fluctuations, fashion trends, production patterns, and shifting population sizes, to mention just a few of the research avenues that have been explored so far.